It’s easy to have a false sense of security when accessing a database with a read-only user. I’d like to talk about how locks work in PostgreSQL, and how this can lead to problems when using read-only users.

Quick definition: I’m defining a read-only user as one which has only USAGE and SELECT privileges on a schema. So they can read the data in the tables, but not modify it in any way.

Locks

PostgreSQL has several types of lock. The only type I’m going to talk about here is table-level locks. As you might guess, these locks apply to the whole table.

There are eight modes of table-level lock, which conflict with each other in different ways. This is effectively a more expansive version of a read/write lock, shown in the table below.

| Read (shared) | Write (exclusive) | |

|---|---|---|

| Read (shared) | ✅ | ❌ |

| Write (exclusive) | ❌ | ❌ |

Here, read locks do not conflict with each other, so any number of these can exist concurrently. Write locks conflict with both read locks and other write locks. When a write lock exists it ensures it is the only lock.

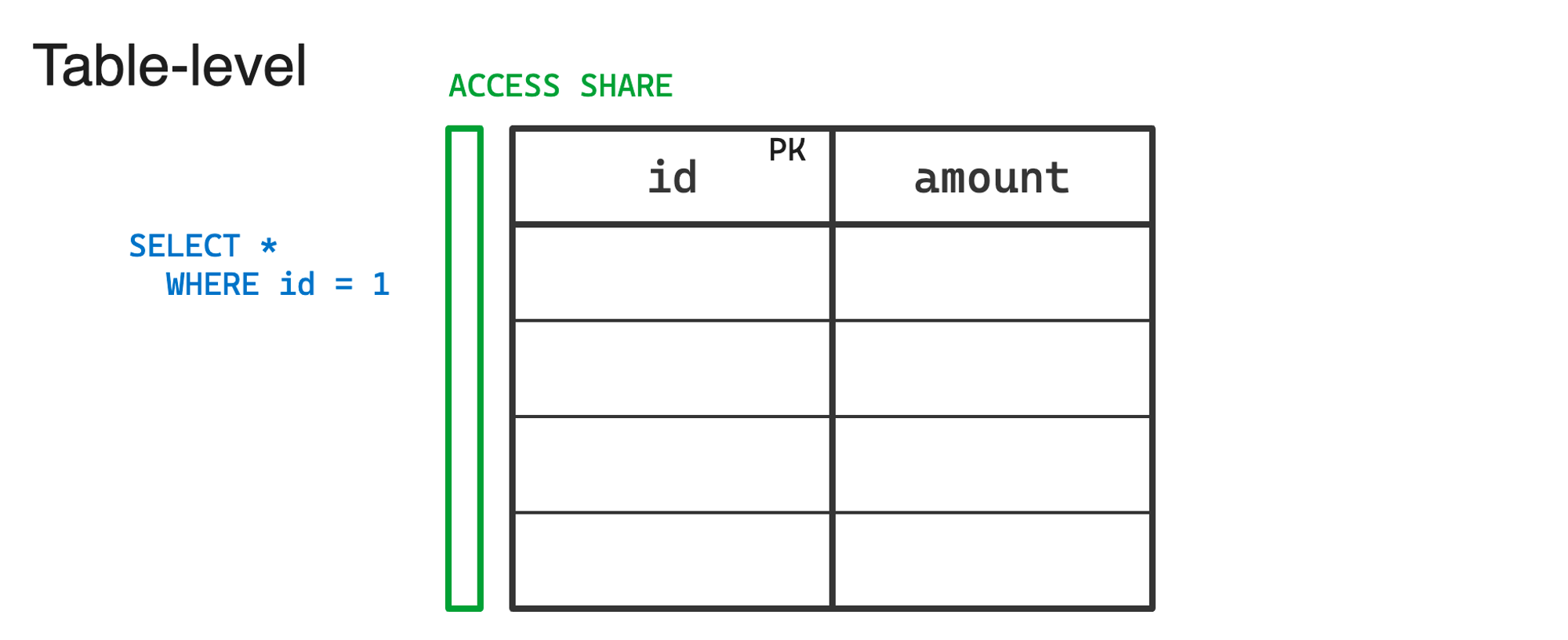

The least-conflicting table-level lock is ACCESS SHARE which is generally taken out by SELECT statements.

A SELECT on a table

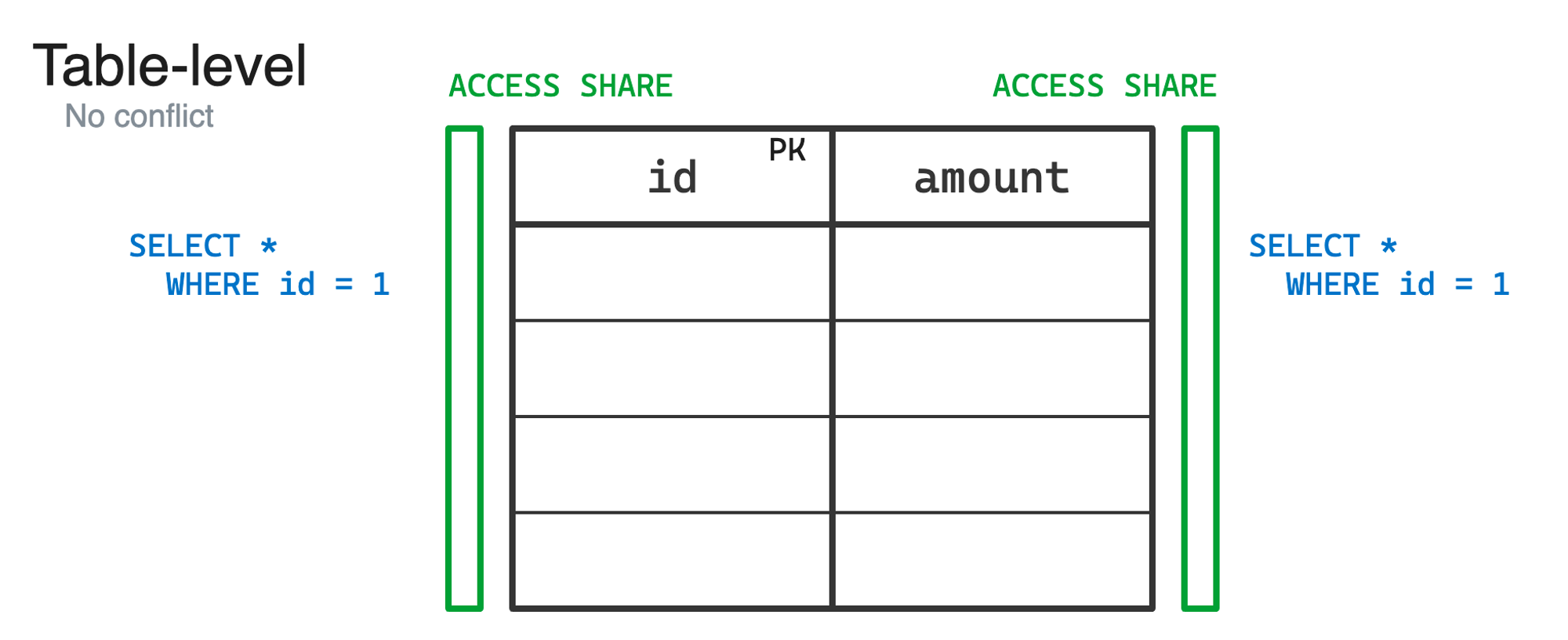

We can have any number of these running concurrently, like so.

Two SELECTs running on a table

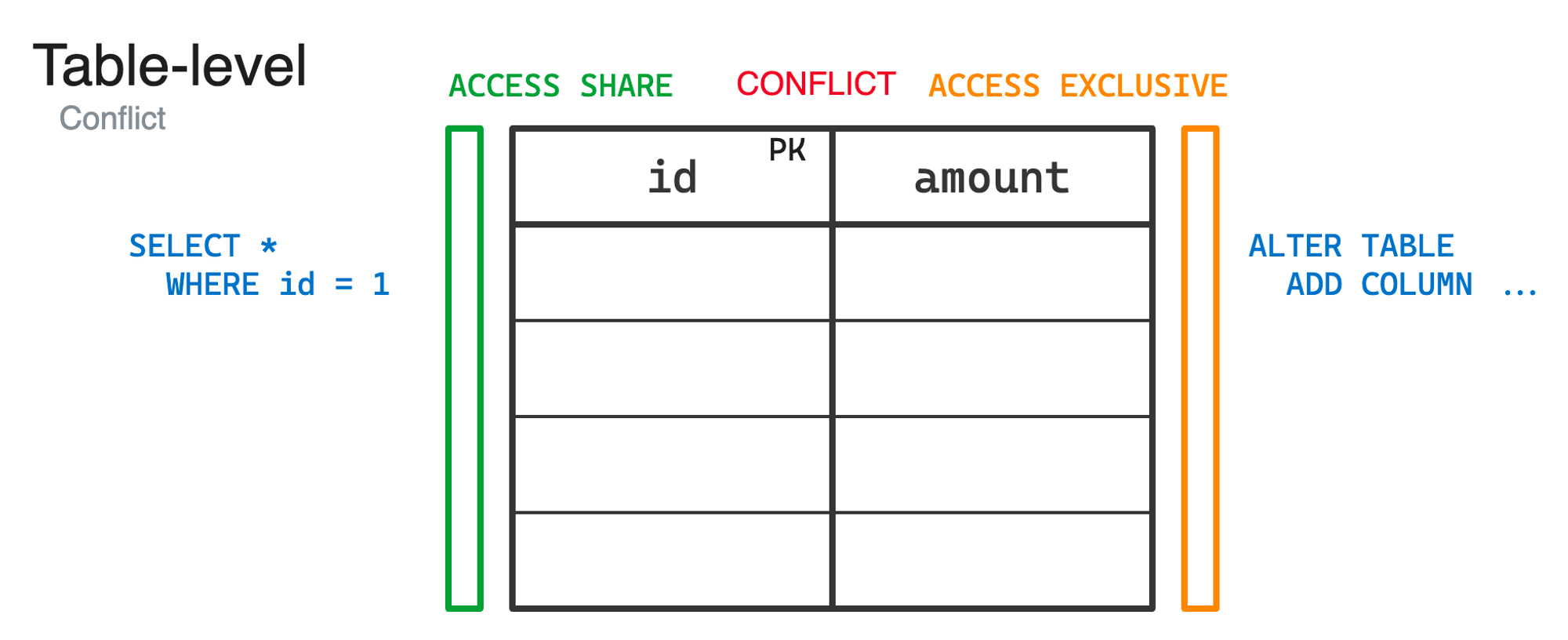

However, these locks conflict with the most-conflicting lock: ACCESS EXCLUSIVE. This is taken out by (most) ALTER TABLE statements. This means we can’t read data in the table at the same time as modifying the structure of the table.

Two SELECTs running on a table

This is the code which decides which lock mode to use for ALTER TABLE, along with some explanations of why that mode is required.

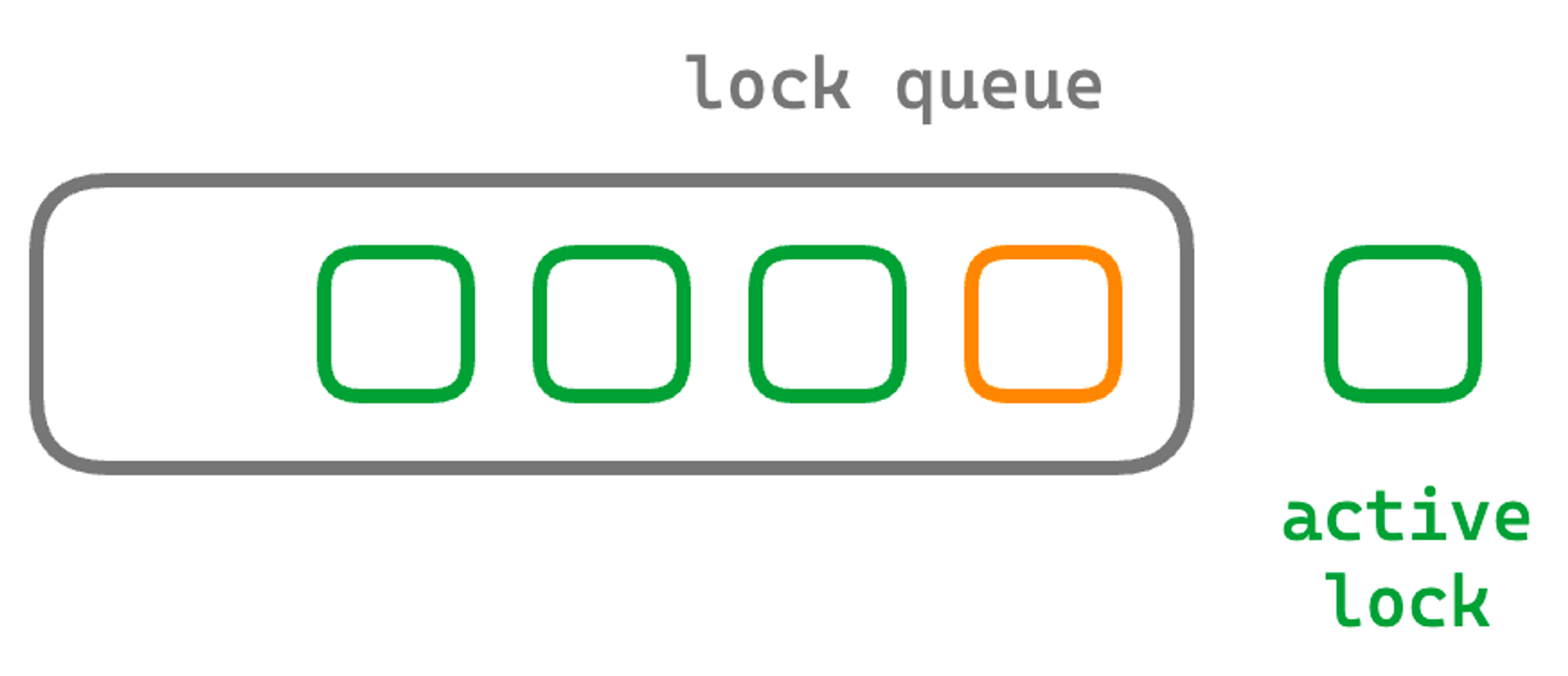

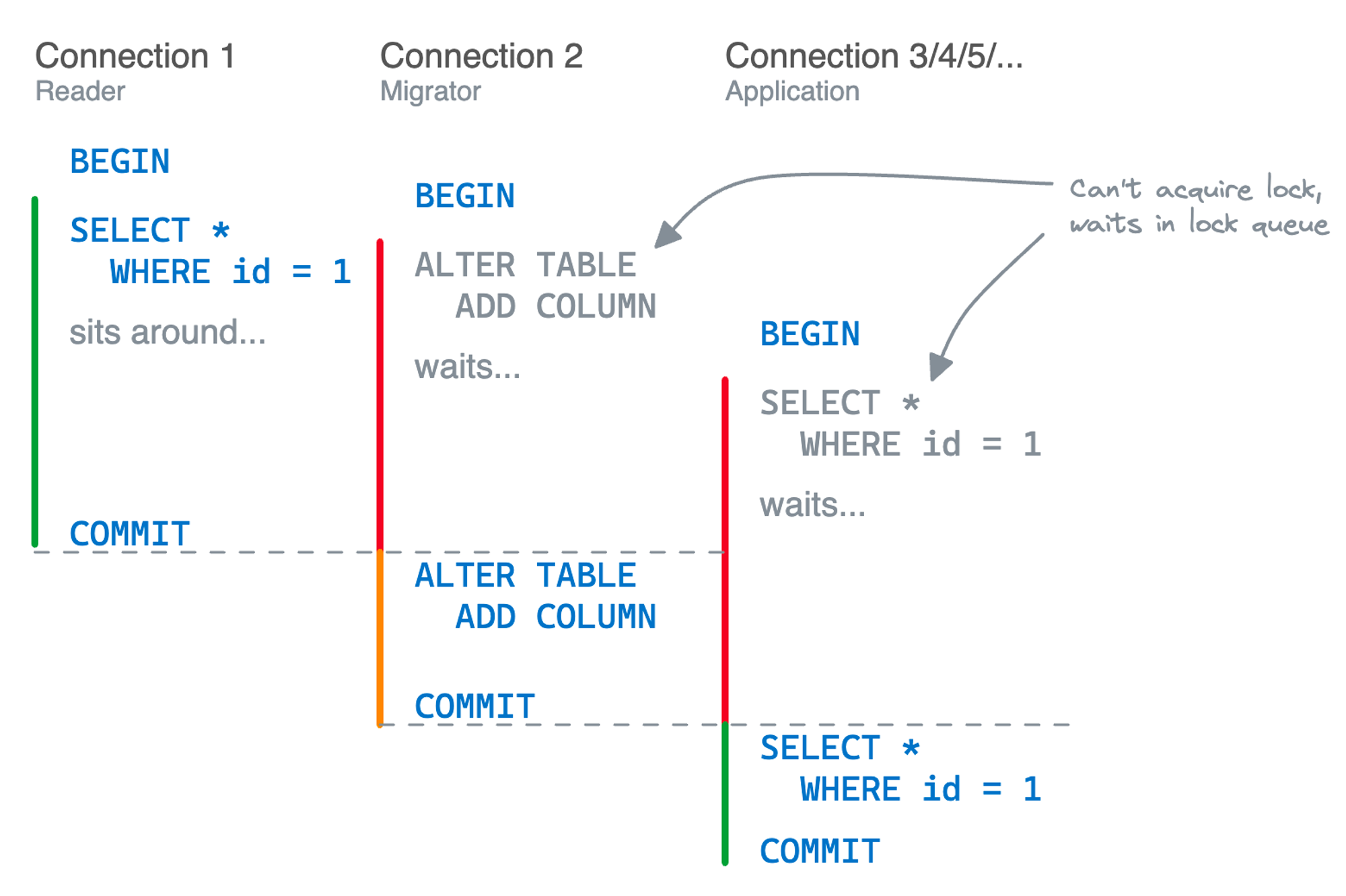

The strategy PostgreSQL uses when trying to acquire a lock on an already locked table is to put the lock request into a queue. This can result in the scenario where an ACCESS SHARED lock exists for a long time, which blocks an ACCESS EXCLUSIVE lock, which in turns blocks all subsequent ACCESS SHARED locks.

Statements waiting in a lock queue

In effect, as a read-only user it is possible to block all table reads.

You might wonder: “why not just let those SELECT statements skip ahead in the queue?”. A reasonable question! If we did this, then what could happen in a busy database is that queries keep coming in, and there is never a free moment to start the ALTER TABLE. It would just be stuck forever. See priority policies on Wikipedia for more discussion.

Example

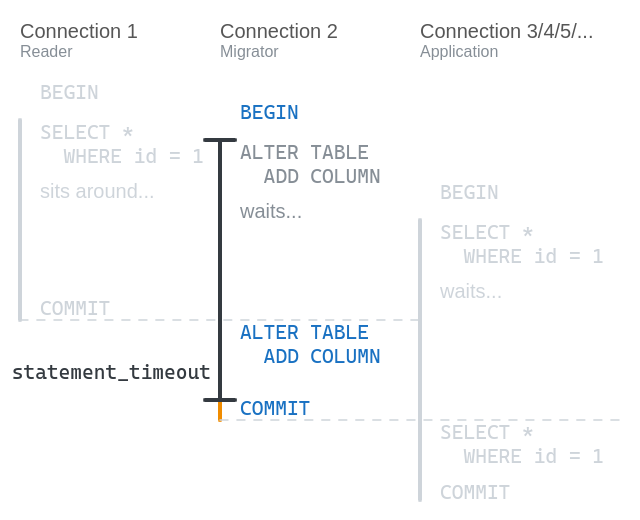

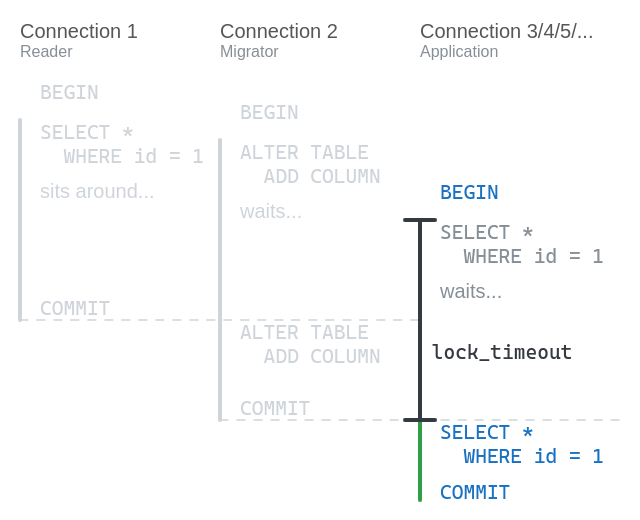

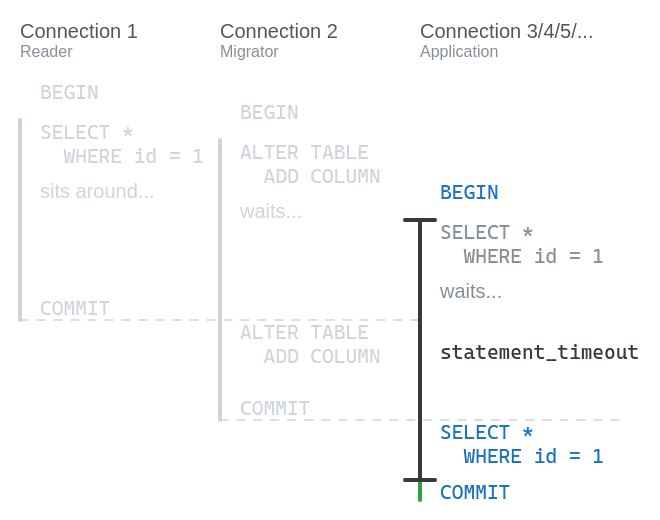

Let’s go through an example. Here, we have three roles:

- The reader – perhaps someone doing some manual inspection of the database.

- The migrator – responsible for performing schema changes.

- The application – responsible for running queries for live traffic.

Imagine a human is using the reader role, begins a transaction, performs a SELECT on a table, then goes to make a coffee.

While they’re making a coffee, someone else deploys a schema migration which does an ALTER TABLE. This won’t be able to run, because it can’t get a lock. So it waits in the lock queue.

Meanwhile the application is still trying to serve production traffic, attempting normal reads and writes. All of these will get stuck in the lock queue behind the ACCESS EXCLUSIVE.

A bad situation!

Oh dear.

Timeouts

One solution to this problem is to use timeouts, of which PostgreSQL offers four:

statement_timeout– Abort any statement that takes more than the specified amount of time.lock_timeout– Abort any statement that waits longer than the specified amount of time while attempting to acquire a lock on a table, index, row, or other database object.idle_in_transaction_session_timeout– Terminate any session that has been idle (that is, waiting for a client query) within an open transaction for longer than the specified amount of time.idle_session_timeout– Terminate any session that has been idle (that is, waiting for a client query), but not within an open transaction, for longer than the specified amount of time.

The first three are the most useful to us here. Generally, we want to prioritise these roles like so:

- Highest priority – application

- Medium priority – migrator

- Lowest priority – reader

That is, we want to make sure that migrators can’t block applications for too long, and that readers can’t block either migrators or applications for too long.

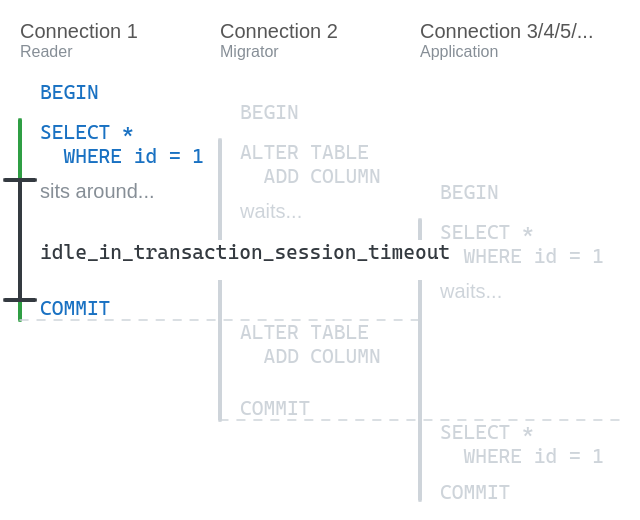

The first thing we can do is make sure no reader transactions hang around holding locks for too long. Two locks are good for that: idle_in_transaction_session_timeout and statement_timeout.

Applying timeouts to the reader

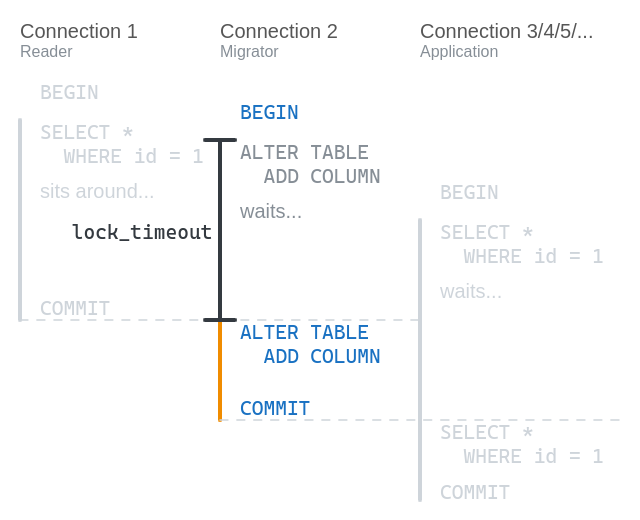

Next, we can make sure that the migrator doesn’t spend too long sitting in the lock queue, or holding any locks itself. We can use lock_timeout and statement_timeout. The statement timeout is arguably enough, but it can be nice to configure them separately, e.g. “don’t wait more than 1 second for a lock, but if you manage to start you have 5 seconds to do your work”.

Applying timeouts to the migrator

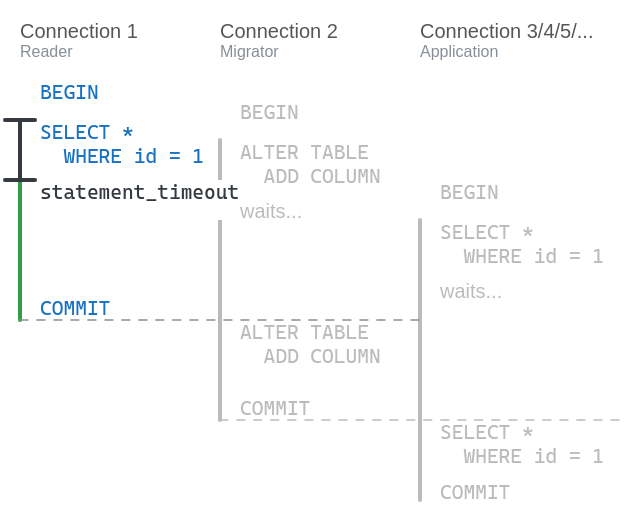

Lastly, we probably don’t want application queries piling up in the lock queue for too long, or taking too long to run. After all, an application could run a long SELECT statement (or let a transaction sit idle having run a SELECT) which would block any ALTER TABLE statements. We would want to use lock_timeout, statement_timeout and idle_in_transaction_session_timeout here.

Applying timeouts to the application

So there you have it. Be careful when running read-only queries on databases!