Let’s imagine a scenario where I’m trying to decide how many chairs I need for my new flat. In this imaginary scenario I live with a partner, and I have two types of chair to choose from:

- A normal chair. This takes up some space in the flat.

- A magic fold-up chair. This takes up space when unfolded, but zero space when folded.

How many chairs do I need?

Well, I live with my partner so clearly I need two, at least. That’s the minimum number of chairs I need. We’ll be using them a lot, so we’ll just go with the normal chairs.

Min. chairs required: 2

We might invite friends or family over for dinner occasionally, so we decide to also get 15 magic chairs. That’s a total of of 17 chairs. More is better, right?

One day we invite round as many friends and family as we can and start putting out the chairs, only to realise we can’t actually fit them all in. We can only fit 12 unfolded chars in the flat. Whoops.

Max. chairs the flat can support: 12

What went wrong?

- We didn’t consider how many chairs we actually need, based on expected number of visitors. We just chose an arbitrary number.

- We didn’t test how many chairs we can actually fit.

What should we do instead?

First, think about how many people we expect to host in total. This is what should inform how many chairs we need.

Second, once we’ve worked out how many chairs we need in total, think about how often we’ll be using these chairs. If some chairs will be rarely used, we can use magic chairs so they only take up space when they’re needed.

Let’s work through an example.

We have two people in the flat full time. The busiest time of year is expected to be Christmas, when four parents will be visiting for dinner. Turns out we don’t have many friends.

Max. expected chairs in use: 6

It’s possible, but unlikely, that one day we’ll host a small party, or have someone else over for Christmas. We don’t want to get caught out, so we’d like another couple of chairs, just in case.

Buffer: 2

Chair capacity required: 8

Now we know how many chairs we need. Nice.

Since we rarely have visitors, we know we only need to keep two chairs around most of the time. So six of those chairs can be magic chairs, to save space most of the year.

Much better.

Now, let’s imagine another example where we already have lots of chairs in the flat:

- 4 dining chairs

- 2 desk chairs

- 2 camping chairs

- a 3 seat sofa

For a total of 11 seats. Based on expected use we worked out we only need 8 chairs to handle all of our expected visitors, including a reasonable buffer for unexpected visitors.

Do we need any magic folding chairs? No. In this case we already have enough to need our needs. In fact, if we do get an extra, unnecessary, magic chair, we face the risk that we won’t be able to fit it in. Which doesn’t sound so bad. But instead imagine if these chairs were really heavy, and when we got it out to use the floor collapsed. The point is, if we don’t test it then it’s a risk because we don’t know what will happen.

Auto-scaling

Alright, the analogy is breaking down a bit by now. In case you hadn’t guessed, I’m not really talking about chairs here. I’m talking about auto-scaling. Specifically, horizontal pod auto-scaling in Kubernetes.

I often see auto-scaling being thought of as a technique to increase resources when under load, with the intention of increasing reliability. However, when misused it can sometimes have the opposite effect of decreasing reliability. Arguably it is better thought of as a way to reduce resource usage when under-utilised, as a way to save costs.

I also see HPAs with arbitrarily high maximum replicas configured, just in case there is a big spike in load. I see several problems with this approach:

- Pods aren’t free. They use resources including CPU, memory, file descriptors, maybe database connections. We need to make sure we have enough of these resources to support the number of pods we want to scale up to. Importantly, we need to test these cases. There are often unknown limits in our infrastructure. We want to find these in a controlled way, not hit them in an uncontrolled way while under peak levels of traffic.

- The numbers aren’t based on the reality of expected load. The numbers in the example above were arbitrary. We should really be thinking in terms of how many resources we need to handle our expected traffic. We should also be prepared for a reasonable amount of unexpected traffic. How much buffer is needed will be context-dependent.

- Simply saying “more is better” is an infinite argument that never ends. One can say: “we have 3 pods, let’s have 2 more on standby just in case”. However the obvious next step is: “we have 5 pods maximum, let’s add another 2 on standby just in case”. Ad infinitum. Again, it is not possible to decide on a sensible maximum without considering the reality of expected load.

To elaborate on 1: I worked on a system built on top of PostgreSQL. PostgreSQL can be fairly constrained when it comes to connections, and from memory we had a limit of 300 on the instance. Each pod had a default limit of 10 connections, each service ran a minimum of three pods for redundancy. We ran more than 10 services. This was a potential problem and we knew it: if every pod filled up its pool of connections then we’d see a lot of errors.

We were happy enough with this risk because traffic was a) quite low, and b) generally uncorrelated between services. The business had multiple products which were related but marketed fairly separately. Some services ran the social network, some served buying tickets, some backed an encyclopedia, and some handled a B2C marketplace. It was possible we’d hit a spike in traffic from all at once, but it never really happened.

That is, until we DoSed ourselves by accident by aggressively crawling the website. Whoops. Predictably, we ran out of connections to the database, with new connections being rejected. If we had auto-scaled on CPU/memory, it would only have made the problem worse had it kicked in.

Now you may be thinking “I don’t over-provision like that” or “I run MySQL, it doesn’t have that problem”. Sure, maybe you don’t have this particular risk. Personally though, I wouldn’t feel confident unless I’d load tested to see what happens when maxing out my resources (whatever they happen to be). We’ll always have to make judgements about risks, but known risks are preferable to unknown risks.

Examples

Let’s look at a couple of examples. We’ll keep things simple by just considering CPU utilisation. We’ll assume we’re running a minimum of three pods for redundancy and each pod has a CPU limit of one CPU core, for a minimum CPU capacity of three cores. We’ll also assume CPU utilisation is directly proportional to incoming traffic.

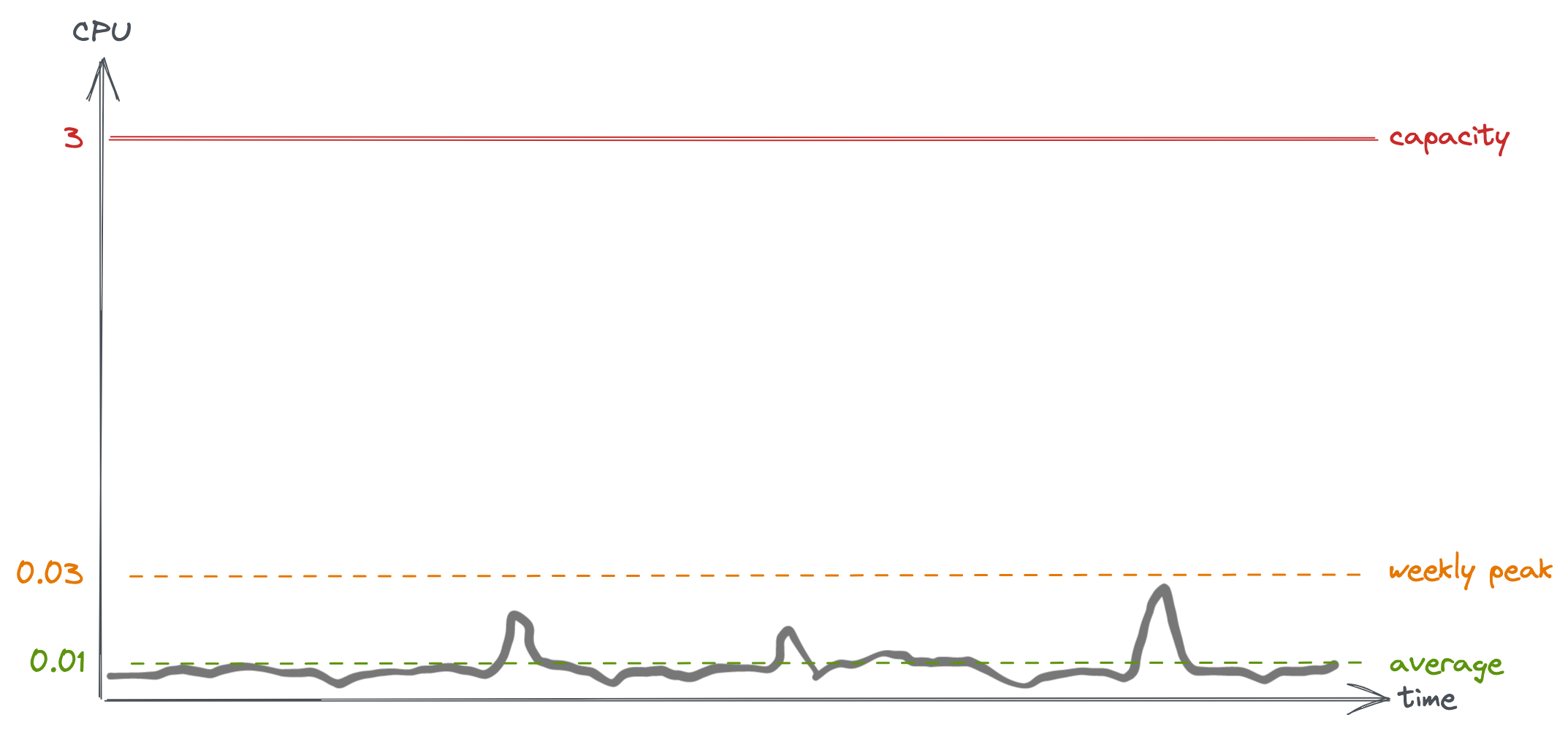

In this first example, we’re using very little CPU, generally around 0.01 CPU cores on average. Weekly peaks reach 0.03 cores. If things go wild and hit 10x our weekly peak, then that’s still only 0.3 cores. If we get 100x our weekly peak, then we start to hit the limit.

Should we auto-scale? That depends on how likely the traffic is to increase 100x unexpectedly. That informs how much of a buffer is needed. Maybe the load is fairly steady, and 2x the normal peak would be a big event. In which case auto-scaling seems unnecessary. On the other hand, if 100x growth is the goal then it makes sense to prepare for it.

CPU load for a quiet service over one week

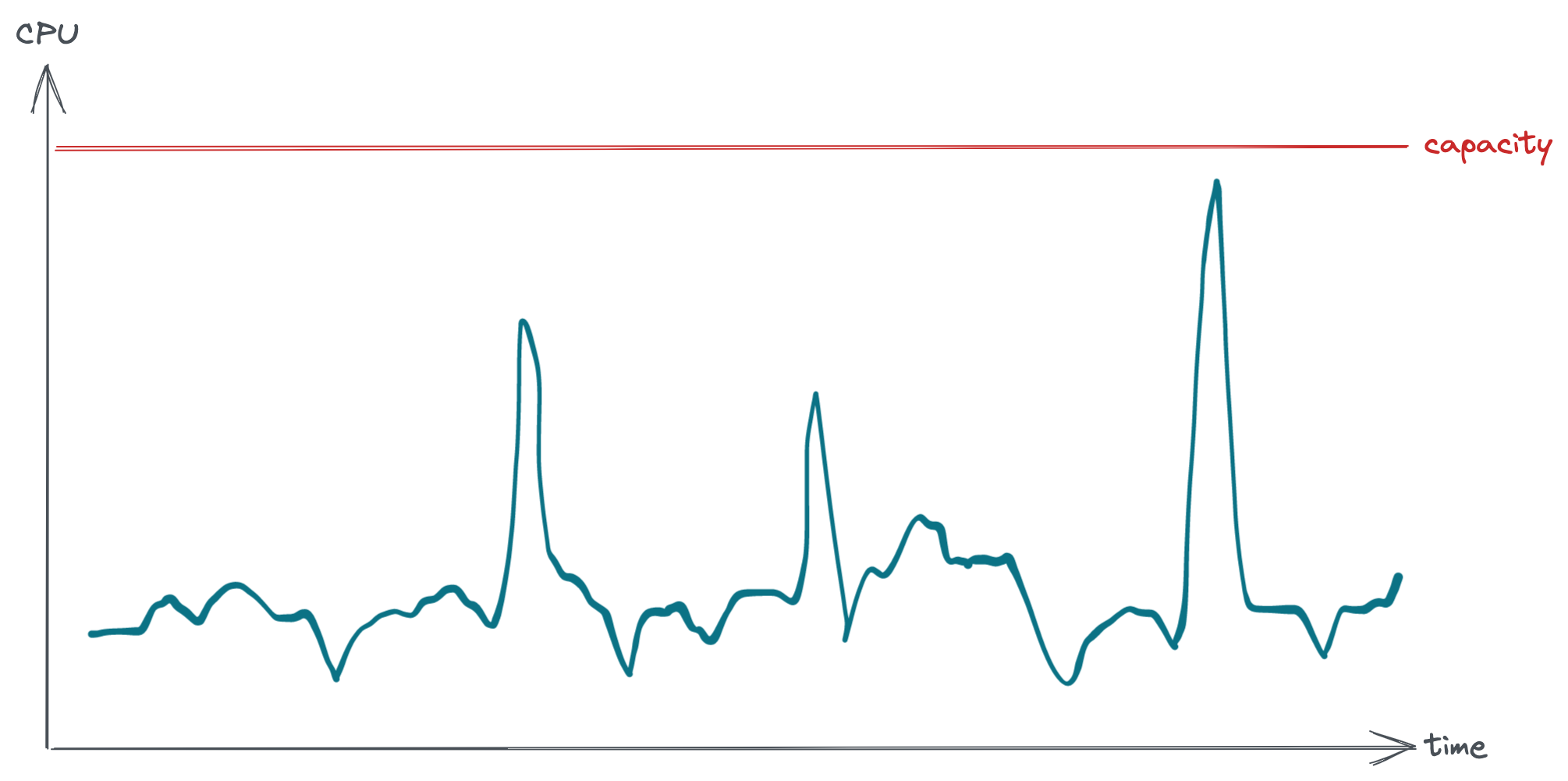

In this next example we see that the CPU utilisation is getting pretty close to capacity, but only for a few peaks over the week. Again, should we auto-scale? Again, the answer is: how much of a buffer is needed? How predictable is the traffic? The maximum traffic would have to be pretty damn predictable to sustain 90% CPU utilisation without worrying. Plus, high CPU utilisation affects request latency, and maybe that’s undesirable. We probably want more pods to handle this traffic, and since most of the week the traffic is much lower we can probably scale down most of the time. This looks like a good candidate for auto-scaling.

CPU load for a busy service over one week

Conclusion

Instead of thinking “we have X pods provisioned, let’s add auto-scaling to scale up, just in case”, I prefer the mental model of “based on expected load we need X pods maximum, can we scale down sometimes to save costs?”.

To summarise:

- Use auto-scaling to scale down, not up

- Base your replica count on real world resource usage

- Consider your maximum replicas to be your default, and test it

I think this mindset shift is helpful, and approaching the problem from this perspective encourages us to build more appropriately scaled systems.