You tried your best and you failed miserably. The lesson is, never try.

– Homer Simpson

Retries are used to increase availability in the presence of errors at the cost of increased latency. The concept seems simple at a high level, but there is a fair amount of complexity hidden inside it. How effective any particular approach is will depend on context, including the pattern of incoming requests and the pattern of failure causing the errors.

Incoming requests might be bursty or consistent, responsive to backpressure or uncontrollable. Failure could be random and transient, or a long-lived correlated outage. It could be caused by the rate of incoming requests (a load-dependent failure) or there could be another cause. These can all have an effect on how retries behave.

I’ve been reading articles by Ted Kaminski and Marc Brooker recently, both of which have wise words on the matter. I was specifically thinking about a case where we have a few services calling each other in series, and what effect retries might have in this scenario. I had an intuition for how this system would behave, but wanted a bit more rigour in my approach. Inspired by Marc Brooker, I made a model to investigate.

Modelling retries

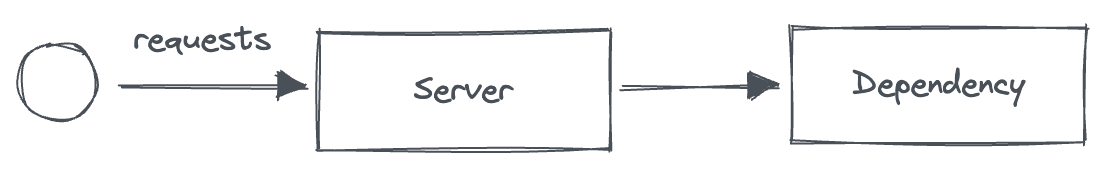

Let’s start with the simplest version of this model. We have a client sending requests to a server, as in the diagram below. Let’s assume we’re providing a service to this client and we can’t control its behaviour. The client is very simple and just sends requests, it doesn’t retry on failure.

Sending requests to a server

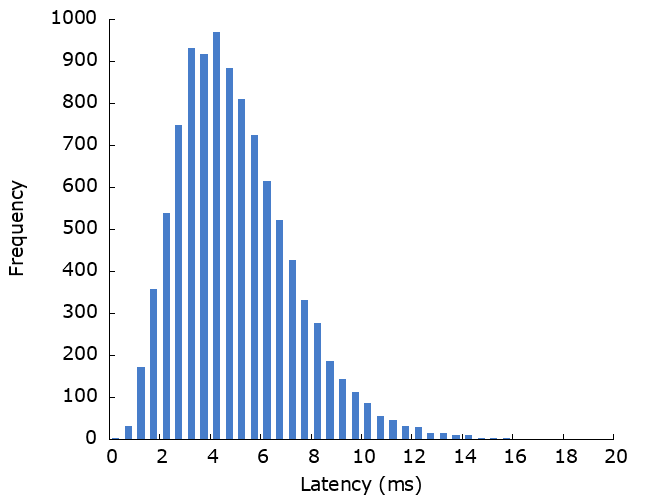

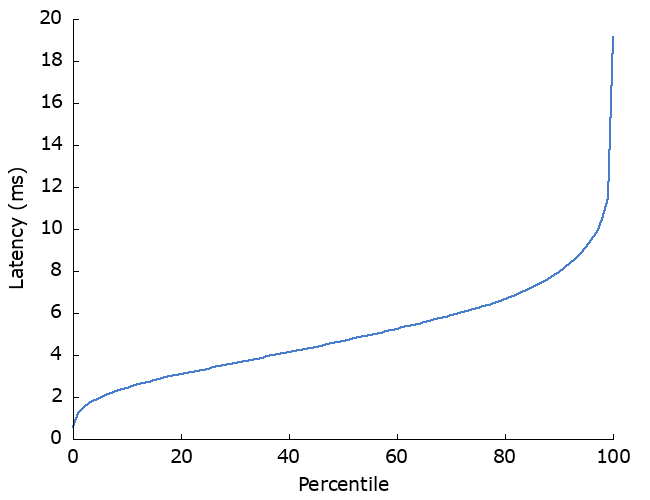

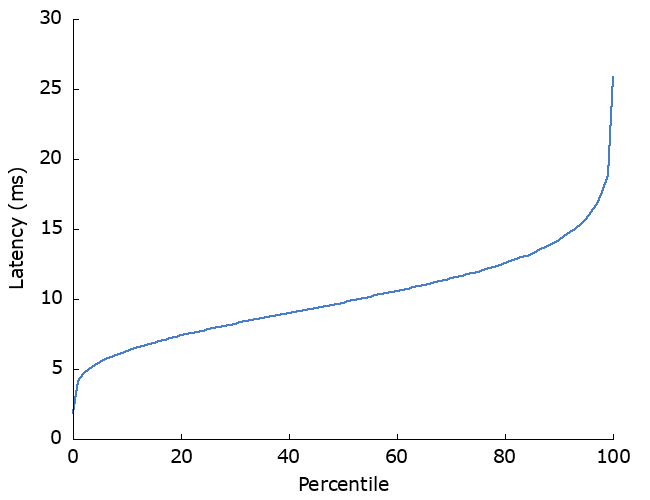

We’ll start off by defining how this server responds to requests. The response times follow an Erlang probability distribution, with a mean of 5ms. Running 10,000 requests we see something like this:

Adding a dependency

What if that server also sends requests to a dependency, like this:

A server with a dependency

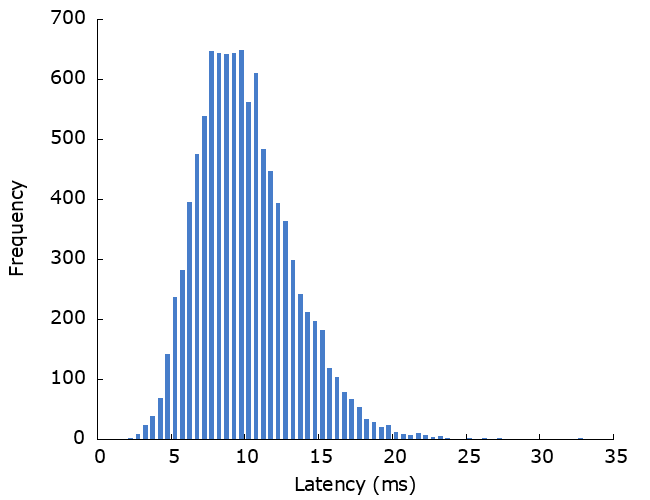

The latencies from the client’s perspective then look like so:

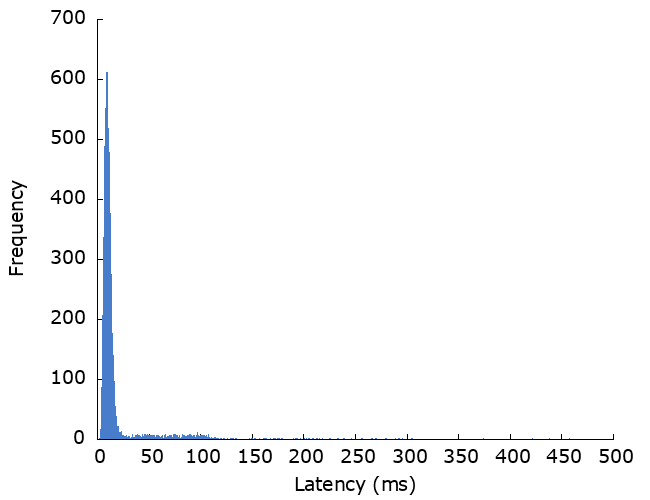

What if that dependency sometimes fails? Let’s model what happens if that dependency has a 10% failure rate and the server retries when a request fails.

Some parameters:

- The dependency fails 10% of the time for first requests.

- The dependency has a recovery time of 2s. The failure rate for retries gown down linearly over this period. In other words, we’re modelling short transient failures.

- The server does up to 3 retries, using exponential backoff with jitter and a base of 100ms.

OK, I made this deliberately bad to highlight how much retries can impact high-percentile latency. 10% failure rate is high, and starting the backoff duration at 100ms is definitely going to have an effect when the mean response time is only 5ms.

There are a couple of other points to note here. Without retries, the success rate would be 90%, and 10,000 requests would be sent to the dependency. With retries, the success rate is better at >99%, but ~11,000 requests are sent to the dependency. Unsurprisingly, this is telling us that retries:

- increase latency (especially at higher percentiles)

- increase availability

- increase load on downstream servers

In most of the systems I work with, the rate of incoming requests isn’t affected by backpressure. A failing system can’t say “please stop for a bit” to customers who are trying to access the site or use the service. In such cases, retries increase load on downstream servers, potentially exacerbating problems.

The model doesn’t (yet?) take into account concurrency or the effect of additional load on failure rate. If it did, it could show how increased load would result in an increased failure rate beyond a certain point.

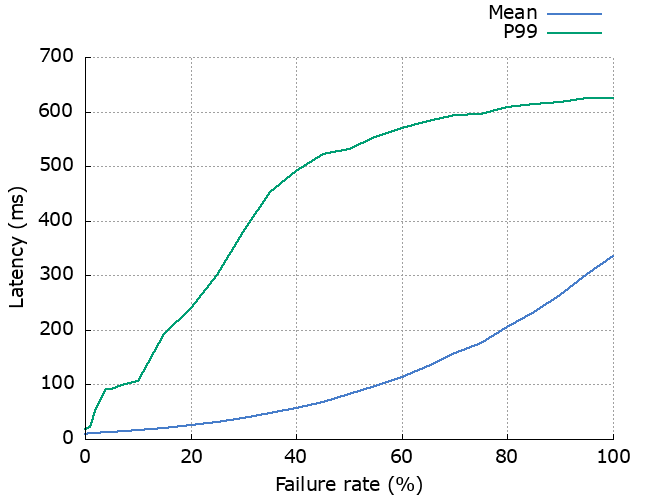

The effect of failure rate

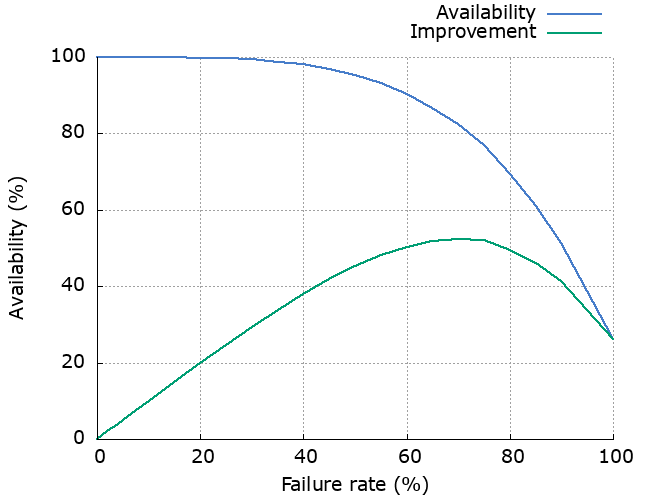

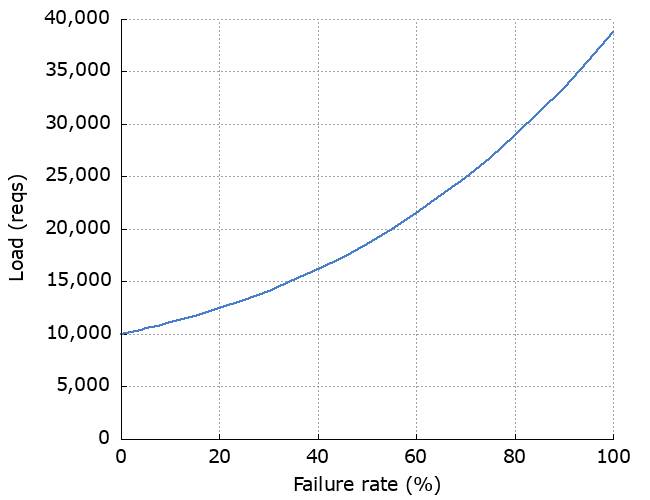

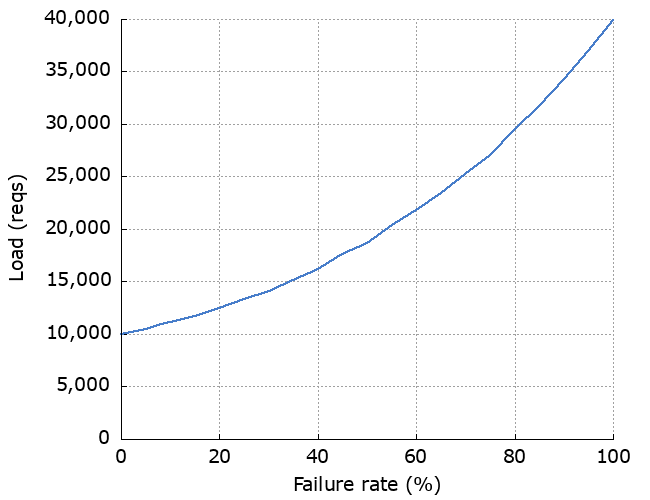

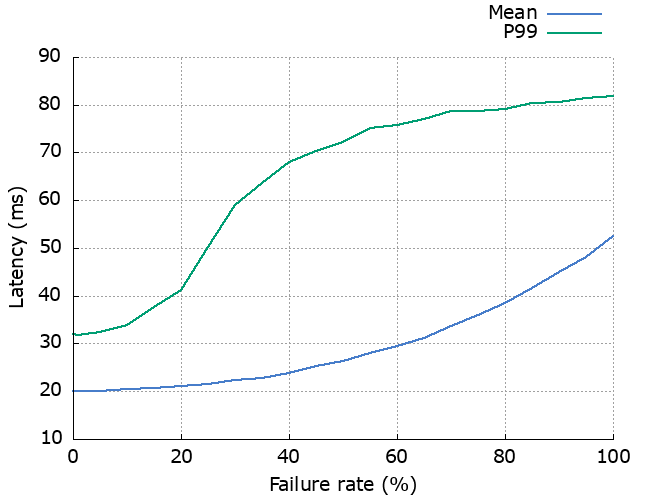

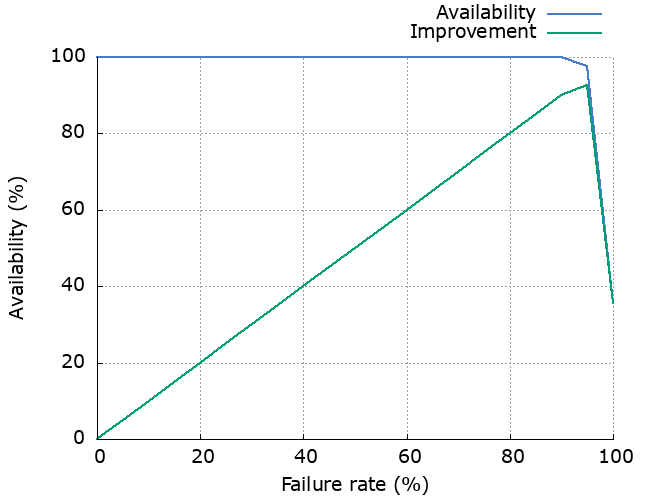

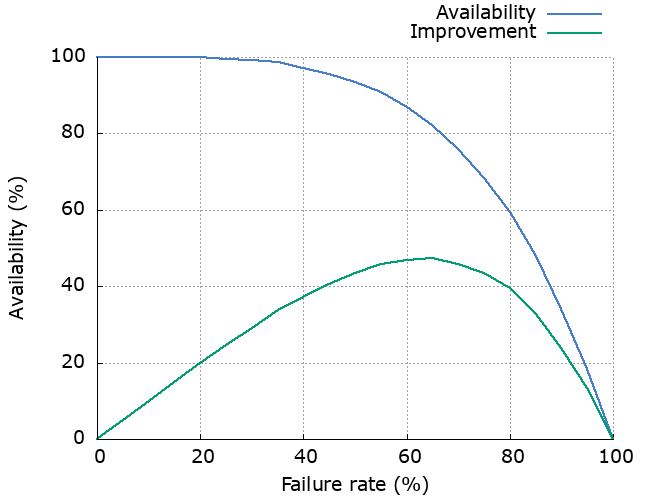

We can look at how much the failure rate of the dependency affects latency, availability and increased load. As we’d expect, increased failure rate causes increased latency, decreased availability and increased load. The “Improvement” line shows how much the availability has been improved by using retries.

Shorter retries

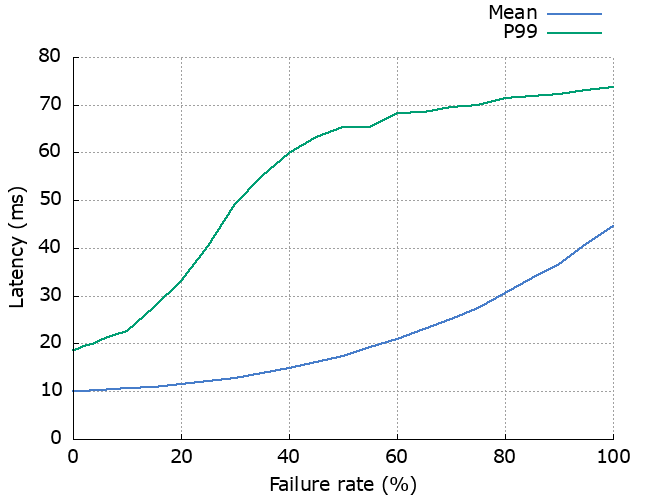

“Those retries are taking too long!” I hear you say. OK, let’s make them a bit quicker and try 10ms instead of 100ms.

The interesting differences here are:

- latency is much better (as expected)

- availability is worse at high failure rates (because we don’t give the dependency enough time to recover)

- load is about the same

If we’re mainly dealing with low rates of short-lived, random failures then this seems like a good trade-off.

It’s worth noting that the decreased latency has two benefits. The first is that we’re providing quicker service to clients. The other is that increased latency can itself lead to failure. If the latency of a dependency goes up 10x, we could have 10x more requests in flight at any given time in the server. This consumes finite resources such as memory, and we might have a few problems if we run out of it.

More dependencies

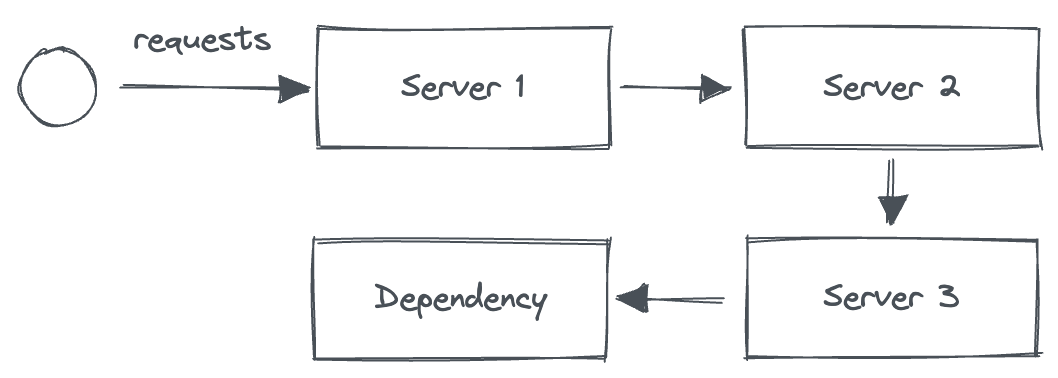

A server with three dependencies

Going back to the original point of this article, what if we have several servers being called in series? I’d like to show what happens using two different strategies:

- every server retries

- only the top-most server retries

Regardless of the end result in terms of latency/availability, I think there are good reasons for choosing option 2. The top-most server knows the high-level operation being performed, and what latency/availability characteristics are appropriate. Lower down servers probably don’t know this, and might get called in different contexts with different requirements. It follows that the best place to make these decisions is in the top-most server.

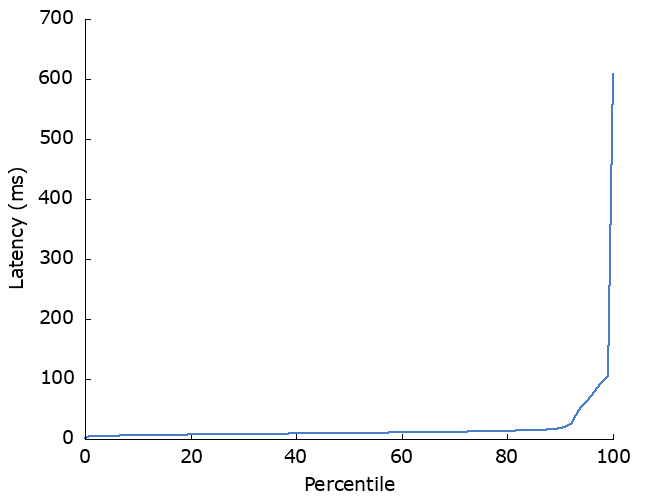

Let’s see how they compare. First: latency.

There doesn’t seem to be a big different here, except at the high percentiles. What happens here is cascading retries. If the dependency is very unresponsive then Server 3 will retry a few times. When then fails, the Server 2 will retry, triggering a whole new set of retries from Server 3. And so on.

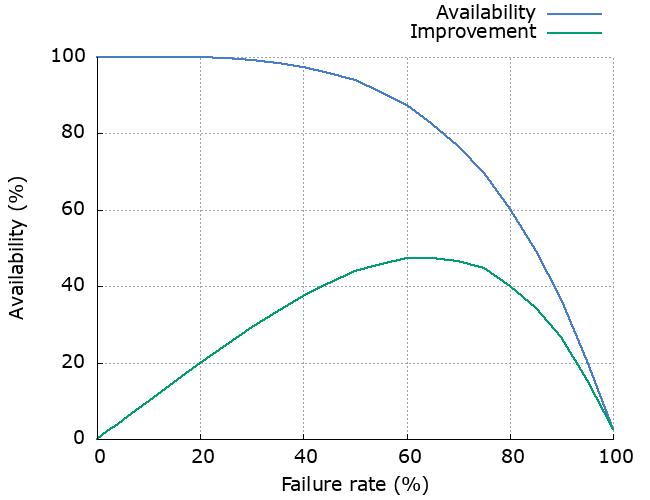

Next, availability.

Because these cascading retries are so damn persistent, we do see increased availability. Note that this is based on the assumption that the dependency failure is short-lived.

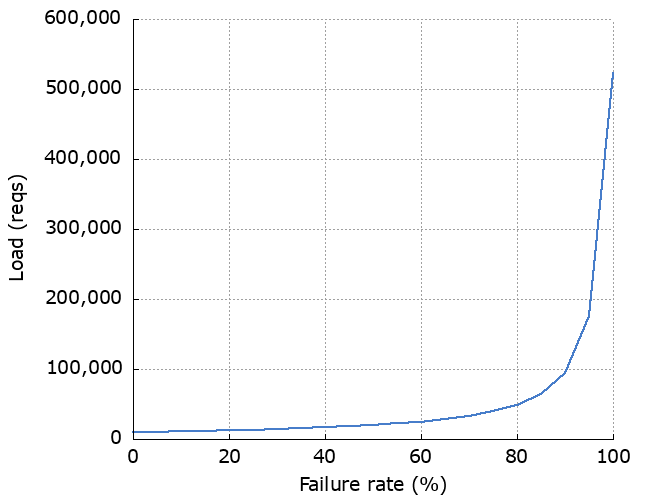

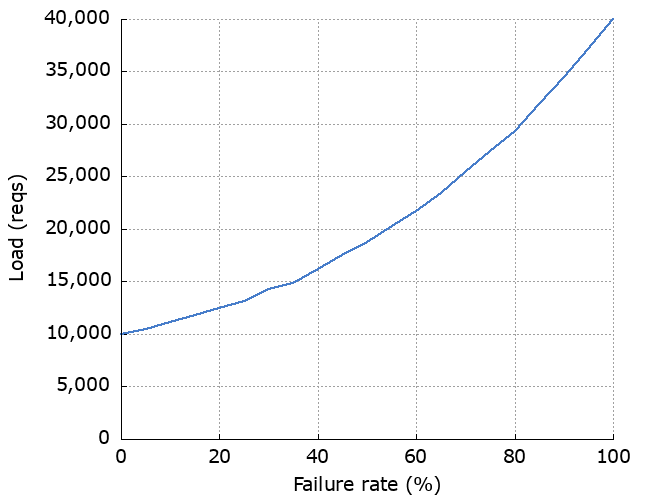

Finally, load.

This is the fun one. Note the difference in scale on the y axes. If we do up to 3 retries, the maximum number of requests we can send to the dependency is:

incoming_requests * (1 + num_retries) ^ num_servers = 10,000 * 4 ^ 3 = 640,000

From 10,000 incoming requests we can end up sending over half a million requests to the dependency. If it was failing because it was overloaded, it ain’t recovering anytime soon. It also introduces a higher risk of metastability problems.

Notably, at low failure rates they both behave pretty similarly. Choosing between the two, I’d pick the one which doesn’t behave pathologically at high failure rates.

While retries are often considered to be a Good Thing, we don’t want them everywhere. In fact, sometimes we don’t want them at all. It can help to zoom out and take a bird’s eye view of a system before choosing whether to introduce them to a service.

Further reading

- The end-to-end principle (Wikipedia)

- By Ted Kaminski:

- By Marc Brooker:

- Metastable Failures in Distributed Systems