A common cause of incidents I see is lack of pagination. Or, more precisely, APIs returning an unbounded number of items. Really it’s the lack of a limit which is the problem, which I think is an important distinction. When returning multiple items, pagination is optional but limits are arguably not.

I’ve seen several variations on the root cause, including:

- The effect of the dataset growing was not considered.

- The dataset was expected to remain small, possibly a fixed size. This assumption was invalid.

- The dataset was expected to grow, but pagination was considered unnecessary, too much effort or too complex to do at the time. YAGNI was invoked, along with “we’ll add it when we need it”. No observability or alerting on numbers of items being returned was implemented.

I’m still not sure what to do about 1 (except talking about it a lot), but 2 and 3 are eminently fixable with a combination of limits and observability.

With that in mind, here’s a quick primer on how I approach pagination (or lack of it). I won’t give a complete overview of pagination methods, or how to design APIs around them, but I’ll introduce the two most popular approaches and how to avoid some common pitfalls.

How to not paginate

Let’s start off with the easy one, which also often happens to be the least well implemented: no pagination.

You have an API, it returns a list of items. Maybe it’s a fixed size, like a list of countries or accepted payment methods. Sure, these lists might change or even grow slightly, but we can probably ignore those cases. Or maybe the dataset is expected to grow, but you still don’t want to implement pagination yet.

There are three things I’d recommend considering:

-

Safety: limit the number of items fetched.

This limit should apply to the number of items returned from the API, and also to any database queries used. You don’t wanna fetch a million rows from the database just to return 10 of them.

If the dataset is expected to grow, this can protect you from the consequences of this growing too quickly. In many cases it can be a good idea to document this limit, so any clients are aware. If you add pagination later, many clients might continue using the non-paginated version forever. Choose your limit wisely.

Even if the dataset size is expected to be stable, adding a limit can be a good fail-safe.

This is a trade-off. You need to choose between a) the risk of returning more items than your system can handle, and b) the risk of returning an incomplete list.

-

Observability: alert when you’re close to this limit.

It’s no good putting in a limit if you don’t know when you’ve hit it. Add metrics, and make sure you’ll know you’re close to your limit before it’s too late.

-

Future-compatibility: make it easy to add pagination later in a non-breaking way.

Design your API with pagination in mind from day one. For example, prefer returning an enveloped response e.g.

{items: [{}, {}]}instead of just an array. This makes it easy to add page information later, and offers can easier transition to existing clients.

Pagination basics

If you do want to paginate, you’ll need to decide how. I’ll compare a couple of approaches. But first, some common aspects.

Page size

Pages have sizes! Often they are configurable, with a limit or size parameter. Don’t let your clients choose a page size of one billion. Either don’t make it configurable, or choose a sensible default and allow the client to request a page size within a specific (and documented) range. If the requested page size is above this range, return an error or clamp the page size like so:

fn limit_page_size(input_page_size: u16) -> u16 {

const MAX_PAGE_SIZE = 100;

min(MAX_PAGE_SIZE, input_page_size)

}

Ordering

If you’re paging through a dataset, you need an ordering. Ideally a strict total order, where every item is either greater than or less than every other item: a < b || b < a. That is, no two items are equal in the ordering. If they were, the ordering would be ambiguous and unstable.

In practice, using unique IDs is helpful here. Imagine sorting by a created_at timestamp. These are generally not unique, two items can be created at the same time. We can disambiguate using a unique ID as a tie-breaker, like so:

ORDER BY created_at DESC, id DESC

Imagine we just ordered by created_at DESC, using the following dataset:

[

{"id": "7ba8", "created_at": "2020-03-01"},

{"id": "9c67", "created_at": "2020-02-01"},

{"id": "4b98", "created_at": "2020-02-01"},

{"id": "7f39", "created_at": "2020-01-01"}

]

If we used a page size of two, either 9c67 or 4b98 would get returned in the first page. We might get the same item, say 9c67, again in the second page, and never see 4b98.

Using offsets

One approach to pagination is using offsets. An offset is a number of rows to skip. In the diagram below, using OFFSET 2 would skip the first two rows and return the second page.

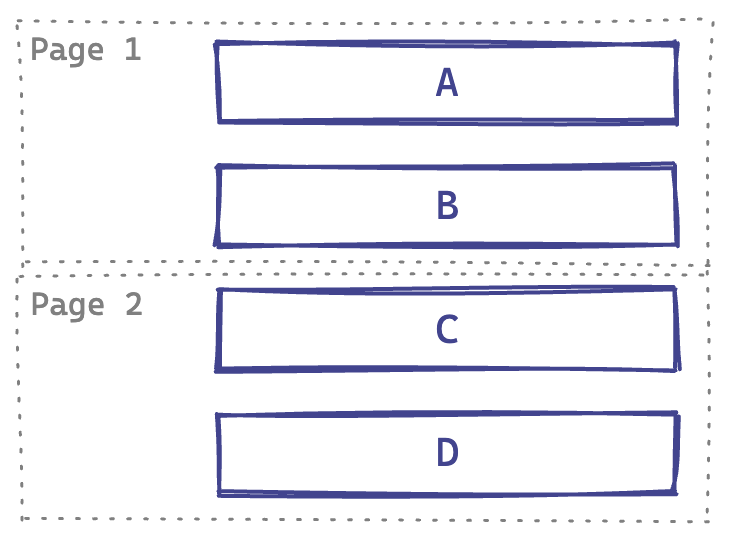

Four items total, page size of two

The offset is 0-based, and we calculate it from a 1-based page number like so: page_size * (page_num - 1). If we want to request the second page, most recent items first, our SQL query would look like this:

SELECT * FROM items

ORDER BY created_at DESC, id DESC

OFFSET 2 LIMIT 2;

This is pretty simple, but has a couple of major drawbacks: unstable page boundaries and inefficient queries for large offsets.

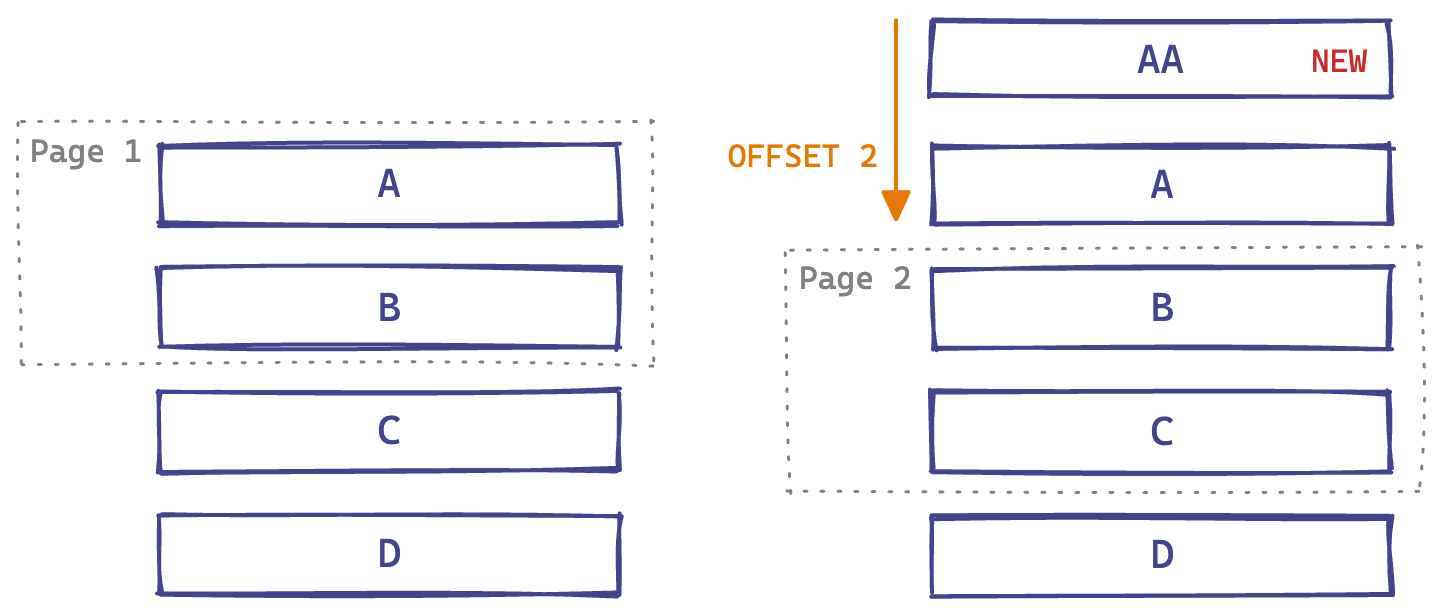

Imagine we request the first page, which returns A and B. Then a new item is written to the database: AA. Then we request the second page, with OFFSET 2. What gets returned? B (again!) and C. But we probably wanted C and D.

Left: Fetch first page. Right: Fetch second page after new item added.

In general, modifications to the list can cause pages to overlap (as above) or gaps between pages (e.g. skipping C if A gets deleted).

Now, imagine we have a large dataset. With a page size of 100, requesting page 101 gives us an offset of 10,000. Generally, databases will not index offsets, especially for arbitrary filters. This means it will need to scan through 10,000 rows before the first item in the page is returned. This can get quite slow!

Both of these problems can be solved by using a cursor-based approach.

Using cursors

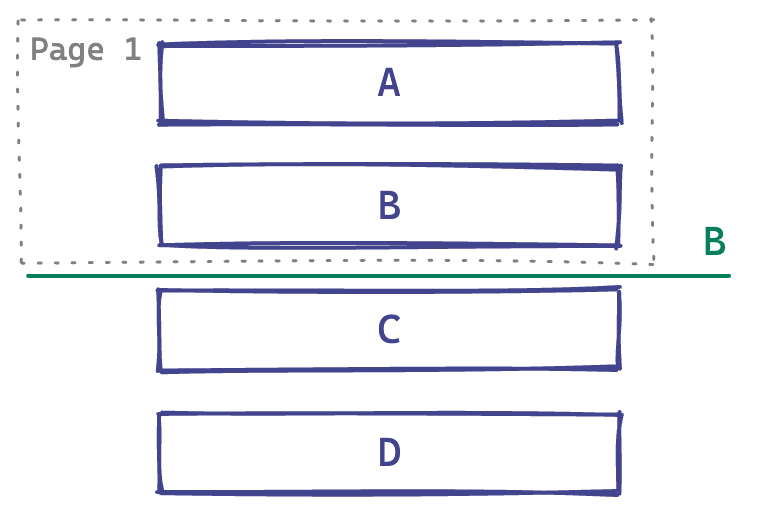

Instead of using an offset to identify page boundaries, which is unstable when the list being being modified, we can instead use a cursor. Much like a text cursor, it is stable when items (characters in this case) are added or removed before or after it.

A text cursor

We use the identity of an item on a page boundary to place our cursor. If we want to get page two in the example below, we can request the two items after B.

A cursor on a page boundary

Going back to our JSON example, we would write the query to fetch page two like this:

[

{"id": "7ba8", "created_at": "2020-03-01"},

{"id": "9c67", "created_at": "2020-02-01"},

{"id": "4b98", "created_at": "2020-02-01"},

{"id": "7f39", "created_at": "2020-01-01"}

]

SELECT * FROM items

-- PostgreSQL syntax

WHERE (created_at, id) < ('2020-02-01', '9c67')

ORDER BY created_at DESC, id DESC

LIMIT 2;

This will always return the next two rows after 9c67, even when new items are added or removed. It’ll even work if the row referenced by the cursor (9c67) is removed.

The other advantage is that the database can jump directly to the start of the page, using the following index:

CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY item_creation_tie_idx ON items (created_at, id);

Comparison

A high-level overview of the two approaches:

| Offset | Cursor | |

|---|---|---|

| Stable page boundaries | ❌ No | ✅ Yes |

| Efficiency | ❌ O(offset + limit) | ✅ O(limit) |

| Implementation complexity | ✅ Low | Medium |

| Skip pages | Yes | No* |

* When using cursors you can’t directly jump to e.g. page 5, but you can jump to an arbitrary point in the list if you can construct a cursor for it. The cursor doesn’t necessarily need to identify a real row. For example you could start from created_at < '2000-01-01' if you wanted to take a look at the 1990’s. This can be useful for paging through an arbitrary time range without having to go back page by page starting from now.